What Happens When a Blockchain Forks? Security, Stability & User Impact

Blockchain is often introduced with one central pillar: immutability. Transactions are final; history cannot be rewritten; it is a single, shared truth. Then people discover forks, and the picture becomes more complex. Chains break down, histories diverge, new tokens emerge, and communities divide. Blockchain is now something that evolves, negotiates, and occasionally fractures rather than […]

Blockchain is often introduced with one central pillar: immutability. Transactions are final; history cannot be rewritten; it is a single, shared truth. Then people discover forks, and the picture becomes more complex. Chains break down, histories diverge, new tokens emerge, and communities divide. Blockchain is now something that evolves, negotiates, and occasionally fractures rather than remaining stagnant.

Forks are not rare cases. They are built into how decentralized systems change. They affect the network security, market stability, user trust, token value, governance, and developer strategy. Understanding what happens when a blockchain forks is essential. This matters for researchers, entrepreneurs, investors, builders, and everyday Web3 users.

In this blog, I’ll explore why blockchains fork, how forks actually work, what they do to security and stability, how they impact users and businesses, and what lessons real-world forks have already shown us.

Why Do Blockchains Fork in the First Place?

Fundamentally, a blockchain fork occurs when nodes on the network disagree on the rules governing their shared ledger. This divergence isn’t typically a glitch; it’s usually the result of human disagreement over the future of the blockchain protocol. The decentralized nature of blockchain, which avoids a central authority, makes consensus on any protocol change crucial. When consensus cannot be universally achieved, the network may split.

Several key factors can lead to blockchain forks:

- Protocol Upgrades and Enhancements: Sometimes forks come from upgrades and new features. As blockchains mature, communities demand better performance, lower fees, or entirely new capabilities. If everyone agrees on the upgrade, it’s smooth. If opinions split, or if some people want faster change than others, a fork can form.

- Security Vulnerabilities and Bug Fixes: The discovery of critical security vulnerabilities or persistent bugs may necessitate changes to the blockchain’s consensus mechanism. If the community cannot agree on a patch or if a fix is controversial, it can lead to a fork.

- Ideological and Governance Disputes: Fundamental disagreements about the core philosophy or governance of a blockchain can lead to forks. Debates around block sizes, transaction fees, decentralization versus speed, or even the ethical implications of reversing a hack are common catalysts.

- Response to Hacks and Exploits: High-profile incidents, such as the infamous DAO hack, can force communities to make difficult decisions about whether to prioritize immutability or intervene. Such events can lead to contentious hard forks as different factions propose distinct solutions.

Forks are a natural part of decentralized governance. They show that the network can adapt, resolve disputes, and pursue different future plans without a central leader.

Types of Blockchain Forks

Blockchain forks are broadly categorized into two types:

- Hard forks

- Soft forks

The distinction lies in their backward compatibility and the severity of the change.

Soft Fork

A soft fork represents a backward-compatible upgrade to the blockchain protocol. This means that nodes that have not yet upgraded to the new rules can still validate transactions and blocks produced by upgraded nodes. Think of it like a software update that adds new features without breaking compatibility with older versions. For example, a soft fork might introduce stricter validation rules or new data structures that older nodes do not support. Soft forks help improve security and add features. Most users need to accept the new rules for it to work well. They are generally less disruptive and less likely to split the community.

Hard Fork

Whereas a hard fork is a radical, non-backward-compatible change to the blockchain protocol. When a hard fork occurs, nodes that do not upgrade to the new consensus rules will reject blocks created by nodes running the new rules, and vice-versa. This incompatibility causes a permanent split. It divides the blockchain into two separate networks. Each chain will have its own history after the fork point. This type of protocol change necessitates widespread agreement and coordination, as it fundamentally divides the network.

Prominent examples include the creation of Bitcoin Cash from Bitcoin and the split between Ethereum and Ethereum Classic.

What Actually Changes When a Blockchain Forks?

When a blockchain forks, particularly a hard fork, the consequences extend far beyond a mere software update. The base of the network’s power structure and operational dynamics undergoes a significant shift. The consensus mechanism, which tells how transactions are validated and new blocks are added, may be redefined. Nodes, which form the backbone of the blockchain networks, must choose which chain to support, leading to a redistribution of hash power (in Proof-of-Work blockchains) or validator stake (in Proof-of-Stake blockchains).

Money and activity don’t stay still either. Liquidity spreads across the new chains as traders, investors, and users pick sides. Even the question of which chain represents the “real” history becomes a heated debate, with both sides claiming authenticity. That brings branding issues, narrative battles, and questions of legitimacy.

Developers and dApps are also pulled into the decision. They need to decide where to build, whether to migrate, or whether to support both chains at once. Entire ecosystems can move or even be born out of a fork.

In simple terms, forks show that blockchains aren’t just ledgers or codebases. They’re living communities with economics, people, beliefs, and software all tied together.

Security Implications: How Forks Change the Attack Surface

Security is often the most critical area affected by a blockchain fork. Splitting a network creates new security vulnerabilities. When a blockchain forks, its total hash rate or validator stake is divided between the competing chains. In Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake, network security depends on the amount of computing or economic power used. A divided network means each resulting chain operates with a reduced security budget, making them more susceptible to attacks.

A smaller, less popular forked chain can be attacked by a group controlling most of the network’s power. This lets them change transactions, block others, or spend assets twice. Forks also open the door to replay attacks. If a hard fork happens without proper replay protection, a transaction you make on one chain can unknowingly be copied onto the other. In practice, that means someone could take a transaction you intended for one network, like sending funds to an exchange, and “replay” it on the second chain.

The result? You might lose assets on both without realizing it. That’s why strong replay protection isn’t optional during a hard fork; it’s essential.

Beyond direct network attacks, forks can create a well-versed environment for social engineering. New tokens, wallet compatibility, and changing network rules confuse users. This confusion makes users more vulnerable to phishing scams and other online attacks. Users might be tricked into sending private keys or signing malicious transactions under the guise of claiming new forked assets or updating their wallet software. Therefore, rigorous security checks and a heightened awareness of potential security risks are crucial during and after a fork. The existing security protocols of a blockchain are tested, and new security solutions may need to be developed or implemented to protect the newly formed networks and their users.

Network Stability: Strengthening or Fragmenting the Ecosystem?

Blockchain forks act as powerful stress tests for the entire ecosystem. Their outcome, whether they strengthen or fragment the network, depends heavily on how the fork is managed and the underlying community dynamics.

On the positive side, forks can help drive innovation and resolve deadlocks. Forks let developers quickly add necessary upgrades, fix bugs, and add new features. They do this without waiting for everyone to agree, which can be slow and hard in decentralized systems. Forks can also help apparent ideological deadlocks, enabling different visions for a blockchain’s future to evolve independently rather than stifling one another. This can lead to a more vibrant and diverse technological landscape, as seen in the creation of distinct ecosystems such as Bitcoin Cash and Ethereum Classic. Forks allow independent development paths. They can lead to a stronger, more resilient blockchain technology ecosystem.

However, forks also carry the significant risk of fragmentation. This can show up in several ways:

- Division of liquidity across multiple chains

- Splintering of developer communities

- Burden on infrastructure providers who must support disparate networks.

Once seamless applications may break on one fork while functioning on another. This can lead to a degraded user experience. Prolonged disputes and uncertainty about forks can reduce user trust. They can also cause significant changes in the market.

Network stability after a fork depends on effective communication. It also depends on transparent decentralized governance. Careful technical execution is essential, too. When a network successfully navigates a fork, it can emerge stronger, with specialized chains catering to different use cases. Conversely, poorly managed forks can lead to lasting division, diminished security, and a weakened ecosystem.

What Forks Mean for Everyday Users?

For the average cryptocurrency holder, blockchain forks are not various technical events; they translate into tangible experiences within their wallets and on exchanges. The most immediate impact is often the sudden appearance of duplicated assets. Following a hard fork, users who held coins on the original chain will typically find themselves with an equivalent amount of the new forked coin on the separate chain. For example, if a user held 1 BTC before the Bitcoin Cash fork, they would have received 1 BCH in addition to their original 1 BTC.

This asset duplication can present both opportunities and challenges. While it can lead to unexpected gains if the new token gains value, it also introduces complexity. Users might temporarily see withdrawals disabled on crypto exchanges while they update their systems to support the new token. They might also encounter decentralized applications (dApps) that no longer function correctly or require updates to operate on one of the new chains.

Forks often thrust users into an active decision-making role. They must discern which chain holds more long-term value, decide how to secure and custody their new assets, and understand evolving legitimacy narratives. Mistakes can lead to irreversible losses due to scams or incompatibility issues with wallet software.

Impact on Developers and Web3 Businesses

Forks create considerable challenges for developers and Web3 businesses. These challenges affect operations and strategy. A fork is not just an ideological event; it requires immediate technical and logistical adjustments. Developers must consider migrating node infrastructure, redeploying smart contracts, updating RPC endpoints, and revising Software Development Kits (SDKs). Choosing which chain to support needs careful technical and business thought. This choice affects transaction speeds and the available decentralized apps.

Businesses must clearly articulate their technical, operational, and philosophical stance on the fork to their user base. This clarity is often crucial for their future direction and reputation. They must decide which chain their product will support, adopt appropriate branding language, and communicate changes effectively to their users. They must also deal with legal and regulatory issues when choosing one fork over another. These rules can vary widely depending on the place.

Forks can also disrupt product roadmaps, leading to paused launches, delayed funding milestones, or renegotiated partnerships. However, they also create new avenues for innovation and market expansion. New ecosystems appear. They attract new developer talent. They generate more token markets and governance opportunities. Companies that handle forks well can grow in the new multi-chain world. They can turn possible problems into advantages.

Case Study: Ethereum vs Ethereum Classic

One of the most pivotal and illustrative forks in blockchain history occurred in 2016 following the DAO hack. The DAO (a decentralized autonomous organization) was an ambitious project built on smart contracts that aimed to operate autonomously, making investment decisions based on code rather than human management. A vulnerability in its code let an attacker drain about 3.6 million ETH into a special child contract. This threatened the whole value of the Ethereum network.

The Ethereum community faced a hard choice. They had to decide whether to keep the blockchain unchangeable, even if it meant keeping stolen funds, or to change history to return the stolen money.

Two primary viewpoints emerged. One camp advocated “code is law,” arguing that any alteration to the blockchain’s history would undermine its fundamental trustworthiness and set a dangerous precedent. The other side posited that Ethereum was a social system first and that the community had the collective right and responsibility to correct an apparent injustice.

Ultimately, the community favored intervention, leading to a hard fork of the Ethereum protocol. This fork reversed the transactions of The DAO hack, effectively returning the stolen ETH to a recovery address. The original, unaltered chain continued to exist and became known as Ethereum Classic (ETC). The forked chain, with the reversal implemented, became the dominant Ethereum (ETH) we know today. This event highlighted the conflict between unchangeable rules and the community’s desires. It showed how forks can fix big problems, but also affect the network’s story and community for a long time.

Are Forks Good or Bad for Blockchain?

Forks are neither inherently good nor bad; they are a neutral governance mechanism that enables decentralized systems to adapt and evolve. They are a strong tool for innovation. They allow essential upgrades, security fixes, and new features without needing everyone to agree right away. Forks let groups with different ideas follow their own plans for a blockchain’s future. This encourages variety and the testing of new ideas across the larger ecosystem.

However, the decentralized nature that enables forks also introduces inherent challenges. Without a central authority to make decisions, reaching an agreement is hard and can lead to arguments. This can split the community and cause lengthy disputes. Forks can cause confusion and market volatility. They can fragment the ecosystem and weaken the security of smaller chains. The cost of this decentralized adaptation is often borne by users and businesses through increased complexity and the need for constant vigilance.

Forks show the ongoing conflict between keeping blockchain data unchangeable and allowing it to change when needed. They demonstrate that consensus is not always guaranteed and that change is constant. While they can expose the untidiness of decentralized decision-making, they also embody the resilience of these systems. Forks help solve conflicts. They also allow blockchains to grow. Forks are essential but can sometimes cause problems.

The Industry Is Learning How to Manage Forks Better

The early days of blockchain forks were often marked by chaos, uncertainty, and significant security risks. However, the industry has matured considerably in its approach to managing these events. Today, there is more focus on transparent governance. This includes clear proposals, thorough testing on test networks, and strong communication with stakeholders, such as crypto exchanges, before a fork.

Developers now add strong replay protection by default in hard forks. This stops bad actors from copying transactions. Wallet providers offer enhanced user interfaces with clear warnings and guidance, making it easier for users to understand and manage their assets during a fork. Better infrastructure tools have made it easier for businesses and developers to support multiple chains.

Forks will keep happening as blockchains grow. But now, they are more planned, expected, and easier to manage. This change shows that the blockchain ecosystem is becoming more advanced. It balances innovation with stability and security.

Ending Notes

Blockchain forks are more than technical events. They show how decentralized systems work. These systems involve code, community, money, and rules. They underscore the challenge and power of achieving consensus without central authority, enabling networks to adapt, innovate, and resolve disputes. Forks can cause serious security problems and affect network stability. However, they also show how blockchain technology can adapt and grow.

Every day, users need to understand forks to protect their assets. They also help users handle complex experiences and make wise choices about their cryptocurrency. Forks require developers and businesses to plan carefully. They also need to be flexible in how they operate. Historical forks have shaped the blockchain landscape. The split that created Bitcoin Cash was contentious. The DAO hack led to the creation of Ethereum Classic. These events show both the disruptive power and the adaptive strength of these networks.

The industry is growing. People are now managing forks much better. They use stronger security measures, more transparent communication, and improved tools. Forks will stay part of blockchain’s future. People have learned lessons that help them manage forks better. They focus more on security, stability, and clear rules for everyone. The ability to navigate these moments of divergence is, in fact, a testament to blockchain’s enduring promise of decentralized evolution.

Date

2 months agoShare on

Related Blogs

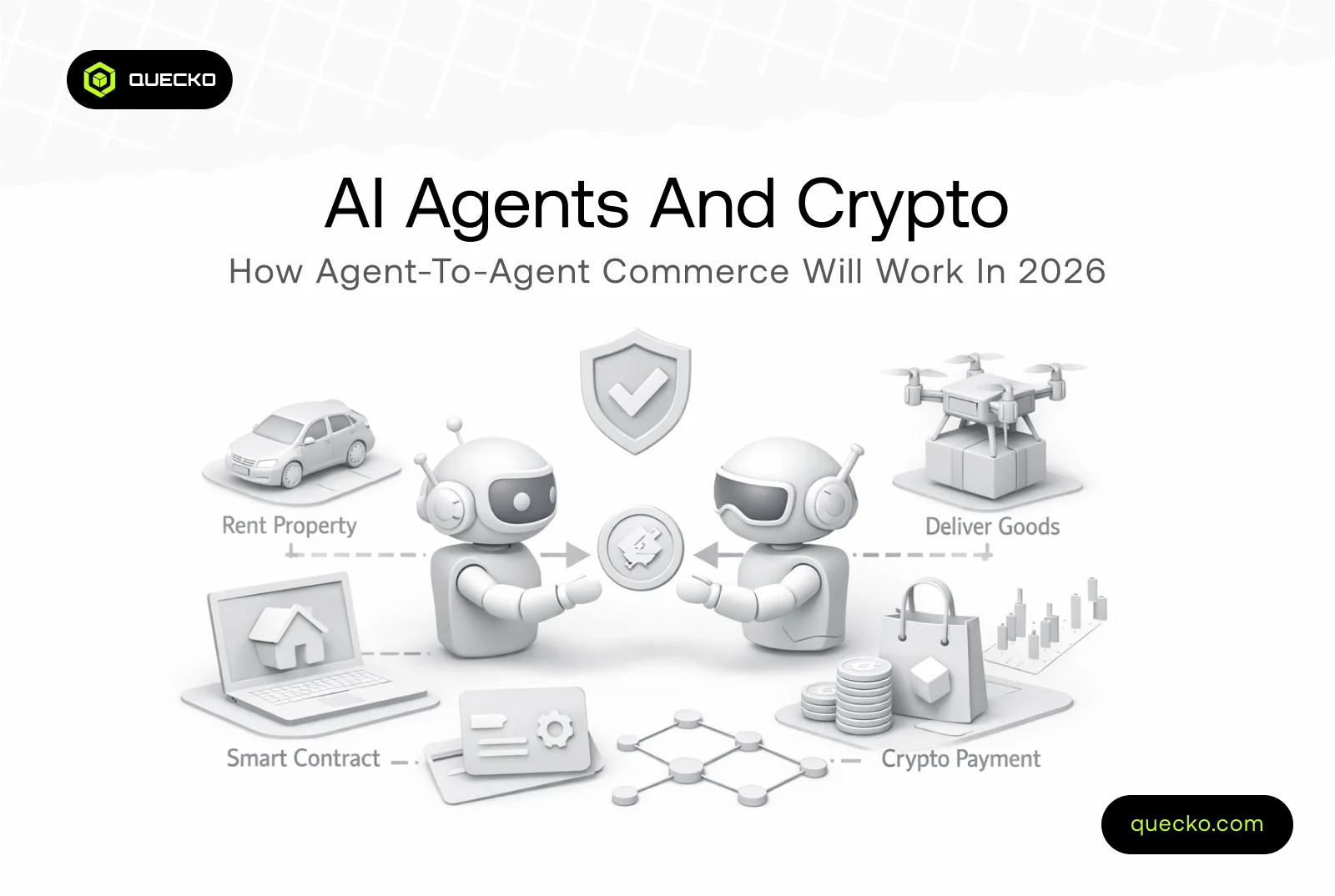

AI Agents and Crypto: How Agent-to-Agent Commerce Will Work in 2026

5 hours ago

Top 5 Blockchain Security Issues in 2026

1 day ago

Decentralized Identity (DID) Beyond KYA: What’s Next for Web3 Authentication

2 days ago

The Evolution of Crypto Marketing: 7 Trends Reshaping Web3 in 2026

3 days ago